Making Your City “EV Ready”

November 1, 2017 | Katelyn Bocklund and Brian Ross | Education

This post was originally published on Great Plains Institute’s website

Electric vehicles (EVs) are gaining traction among consumers, governments, and automakers as battery prices fall and the benefits of EVs increase. Within the last year, virtually every major automobile manufacturer has announced plans to transition to electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles. As cities look to capitalize on the opportunity that EVs can bring, from lower maintenance costs for consumers to better air quality for residents, they also must lay the groundwork for their communities to become ‘EV ready’.

With battery prices coming down, EVs are already among the lowest total cost of ownership vehicles in the passenger car market and will continue to become more affordable for the average consumer. In addition to low maintenance and fuel costs, EVs also offer quiet operation and zero tailpipe emissions, making them a popular choice for both environmentally and economically savvy consumers. Moreover, EVs can help cities meet air quality goals (particularly in low-income neighborhoods along major highways and freeways), save money in city fleets, put downward pressure on taxes, limit cities’ exposure to volatile oil and gasoline prices, and more. In an era where an increasing number of cities are setting local goals for reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, facilitating EV deployment is becoming a vital tool in cities’ toolbox to achieve energy and sustainability goals.

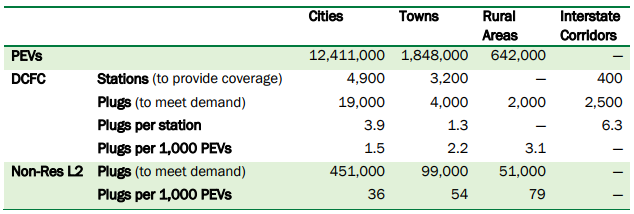

However, more EVs on the road will require more infrastructure and support, and cities can (and should) play a huge role in shaping this future. According to a recent analysis published by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) that examined the amount of infrastructure needed for an EV market transformation, cities will need 4,900 Direct Current Fast Charging (DCFC) stations while interstate corridors will only need 400 DCFC stations.

Summary of Station and Plug Count Estimates to meet demand of 15M PEVs in 2030. Source: National Plug-In Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Analysis (U.S. Department of Energy).

Cities have tremendous influence over how and where infrastructure is built and serve as a critical and necessary partner in the market transformation effort to make EVs a significant part of the nation’s passenger car fleet. Therefore, cities need to be “EV-ready” in policy, regulation, capital improvements, and in planning for public and private infrastructure. The Great Plains Institute (GPI) has identified five principles for what constitutes an EV-ready city:

1) Policy: Acknowledge EV benefits and support development of charging infrastructure

2) Regulation: Implement development standards and regulations that enable EV use

3) Administration: Create transparent and predictable EV permitting processes

4) Programs: Develop public programs to overcome market barriers

5) Leadership: Demonstrate EV viability in public fleets and facilities

1) Policy: Acknowledge EV benefits and support development of charging infrastructure

The comprehensive plan or master plan is the city’s primary policy document, providing the foundation for development regulations, public infrastructure investments, and economic development programs. Prioritizing EV use and development of EV charging infrastructure in the comprehensive plan or master plan enables EV market transformation and city decision-making on EV-supportive programs and regulations. Policies on how your city will support the developing technology can fit under a single chapter of the plan (such as transportation) or be implemented throughout the plan (transportation, housing, economic development, land use, etc.).

In Practice:

Stoughton, Massachusetts. Comprehensive Master Plan: Phase II: Assessment, Recommendations and Implementation Plan. In their 2015 Master Plan, the forward-thinking City of Stoughton, Massachusetts made sure to include language on EVs and supporting infrastructure. Included in the plan’s energy and sustainability sub-section is language that encourages “Maximizing the efficiency of municipal vehicles, supporting electric vehicles…,” as well as general language on improving the community’s walking and bicycling environment. The plan also mentions a key factor of institutional support for EVs in Stoughton: Their Planning Board requires EV charging stations in all new residential developments that include large amounts of parking.

Watertown, Massachusetts. Watertown Clean Energy Roadmap (2014). The City of Watertown’s recent Clean Energy Roadmap includes “Developing Electric Vehicle Charging Station Infrastructure” as one of its 11 core clean energy strategies. This robust, six-page section is an excellent example for other cities to follow, for several reasons. It includes four concrete objectives for the city in relation to developing EV infrastructure, background on the state of EVs in the U.S., as well as the status of electric charging infrastructure (and types of chargers) in the state of Massachusetts. The section also includes statistics and background on the three main types of chargers, the benefits and risks of developing this infrastructure, a cost-benefit analysis in relation to various stakeholders, and more.

2) Regulation: Implement development standards and regulations that enable EV use

Adopting ordinances that support the use of EVs and incorporate electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE) in development and redevelopment is a critical step in becoming an EV-ready community. In particular, parking standards provide a unique opportunity to create EV-ready buildings and commercial facilities. Multi-family housing, commercial facilities, and mixed-use development can be designed to accommodate the transition to EVs and capture a variety of societal benefits, including enabling additional solar or other local energy development. Flexible or alternative development pathways, such as planned unit developments, can incorporate EVSE installation requirements. For retrofitting existing buildings, clear and consistent regulations allow EV developers to know what steps are required to install EVSE. Regulations should facilitate market expansion and transformation, while acknowledging uncertainty about how technology will develop. For instance, while many types of chargers exist, there are currently no universal chargers that all vehicles can plug into without an adapter (e.g., Nissan Leafs cannot use Tesla Superchargers).

In Practice:

Washington State. The State of Washington requires many local governments to allow EVSE in most zoning districts and enables local incentive programs for market transformation (RCW 35A.63.107). Many local governments have incorporated required EV-ready parking standards in local ordinances, including both large cities and small cities and counties. The City of Mountlake Terrance takes requires new development (larger than 10,000 sq ft of building space) to go beyond being EV-ready and include EV charging in a specific percentage of parking spaces (ranging from 1-10%, depending on the type of facility). Other communities take the simpler, required approach by creating a clear as-of-right path for installing EV charging infrastructure. Some communities also require signage identifying EV charging locations and restrict who can use those parking spaces.

Minnesota. Several cities in Minnesota are starting to incorporate or encourage EVSE installation requirements in large commercial or mixed-use development. The City of Golden Valley recently modified its Planned Unit Development (PUD) ordinance (City Code Section 11.55) to include amenity points for electric charging infrastructure, and required a recent project to include EV charging as a condition of design approval. Saint Paul’s Sustainable Building Policy requires all new building or rehab projects receiving more than $200,000 in public assistance to meet an approved sustainable building rating system. These rating systems (LEED, Minnesota B3) encourage or require a set number or percentage of parking to have electric charging.

3) Administration: Create transparent and predictable EV permitting processes

Standardized permitting processes that directly address EVSE allow contractors and city staff to know exactly what information and documentation is needed to install EVSE. Having a standardized, consistent, permitting process reduces time spent on acquiring permits and conducting inspections for both developers and city staff. Permitting processes may need to be updated to best reflect changing industry best practices. Additionally, if a permitting fee is assessed, it should cover the cost of the local government review and inspection costs.

In Practice:

New York. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) offers planners and municipalities best practices for municipal codes and permitting practices to encourage the use of charging stations. Permitting strategies discussed in Residential EVSE Permit Process: Best Practices include labeling EVSE as “minor work”, allowing online permitting applications, streamlining inspections, and publishing installation guidelines that reflect permitting and other local regulatory standards.

4) Programs: Develop public programs to overcome market barriers

Local governments regularly create and manage programs to remove market barriers or mitigate for market failure that prevents desired private sector development. These same tools can be applied to encouraging EVSE in development or public spaces where such development would not otherwise occur. The simplest actions are to enable EV use by installing public chargers at public buildings or in public spaces, where the local government has direct authority regarding infrastructure development. More complex tools include economic development programs such as incentives or financing for desired development, providing public infrastructure that supports public goals, and assembling financial or land resources that will achieve desired private sector investment. All these tools can be used to enable and encourage incorporation of EVSE in private sector development.

For example, several cities in Minnesota have added EV charging facilities in public parking lots to publicly recognize EVs as a viable transportation option and to facilitate market transformation efforts:

- Eden Prairie has level 2 EV charging at its City Hall.

- Saint Paul has incorporated over 40 EV charging stations into parks and public parking ramps

- The Metropolitan Airport Commission has added EV charging parking spaces to its long-term parking facilities.

- The City of Pine City worked with local businesses to install an EV charger downtown and signage directing traffic from Interstate 35. EVSE can be required as part of Green Building program standards, which has been implemented in Saint Paul and St. Louis Park.

In Practice:

Elk River, Minnesota. The City of Elk River partnered with Elk River Municipal Utilities to provide the community’s first public EV charging station, which was completed in 2017. Currently, the station offers Level 2 charging for two vehicles at a time, but the City and ERMU have plans to install more chargers in the near future. The station can be found along Main Street, which makes it convenient for EV owners exploring downtown Elk River as well as those that need a quick charge from Highway 10 or Highway 169.

5) Leadership: Demonstrate EV viability in public fleets and facilities

Cities can boost EV adoption in the private sector by demonstrating how EVs work in their own fleets. By incorporating more EVs into fleets, cities save money over the life of the vehicle, put downward pressure on local taxes, reduce air pollution, and increase energy independence. More importantly, however, integrating EVs into public fleets demonstrates the market readiness of EVs. Public investment demonstrates that EVs can replace conventional cars. Moreover, local governments frequently look to their neighboring cities to assess how to address market trends and new technology, creating opportunities for leadership communities to demonstrate viability.

In Practice:

Saint Paul, Minnesota. In Spring 2017, the Minnesota Department of Administration partnered with the University of Minnesota, the Metropolitan Council, Ramsey County, and the City of Minneapolis to purchase 22 Chevy Bolt EVs at a discounted price. Commissioner Matt Massman of the Department of Admin expects that the state will save $5,000 per vehicle in operating expenses over the life of the vehicles. Local governments in Minnesota are now able to purchase a variety of EV models at the discounted price through the state contract.

New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 2016, New Bedford applied for and received $206,000 in grant funding through Massachusetts’ Electric Vehicle Incentive Program to increase EVs in its fleet by 25 percent. At the time, this move gave the city naming rights to proclaim it the largest electric-vehicle fleet of any municipality in Massachusetts. Out of 70 vehicles, 19 were leased Nissan LEAFs used by the health and school departments.

By practicing the five EV-ready principles, cities can meet demand for new infrastructure, significantly grow EV adoption, and capture the community and individual benefits of lower operating and maintenance costs, zero tailpipe emissions, and energy independence.

Note for Minnesota cities: The Great Plains Institute’s efforts to increase EV adoption and expand charging infrastructure are currently focused in Minnesota and the Midwest. The Minnesota GreenStep Cities program, which assists cities in meeting sustainability goals and documents cities’ progress, is in the process of documenting EV best practice actions for cities consistent with the five principles listed above. The best practices will incorporate the evolving industry standards and offer a pathway to help cities become EV Ready. GreenStep Cities is hosting a workshop on EVs in January that will describe how to become EV Ready. Click here for more details on the agenda and to register. GPI partners with several state agencies, nonprofits, and the League of Minnesota Cities on program development and implementation.